Mormon Flash Mob

So what if you were just standing around and suddenly the person standing next to you suddenly began singing. Well, it might sound something like this:

So what if you were just standing around and suddenly the person standing next to you suddenly began singing. Well, it might sound something like this:

Yeah, right.

In any case, this is galling. And so New York centric as to be self-parody. No wonder this rag sold for $1.00 — that’s the entire rag, including building, desks, copiers, and kool-aid stand.

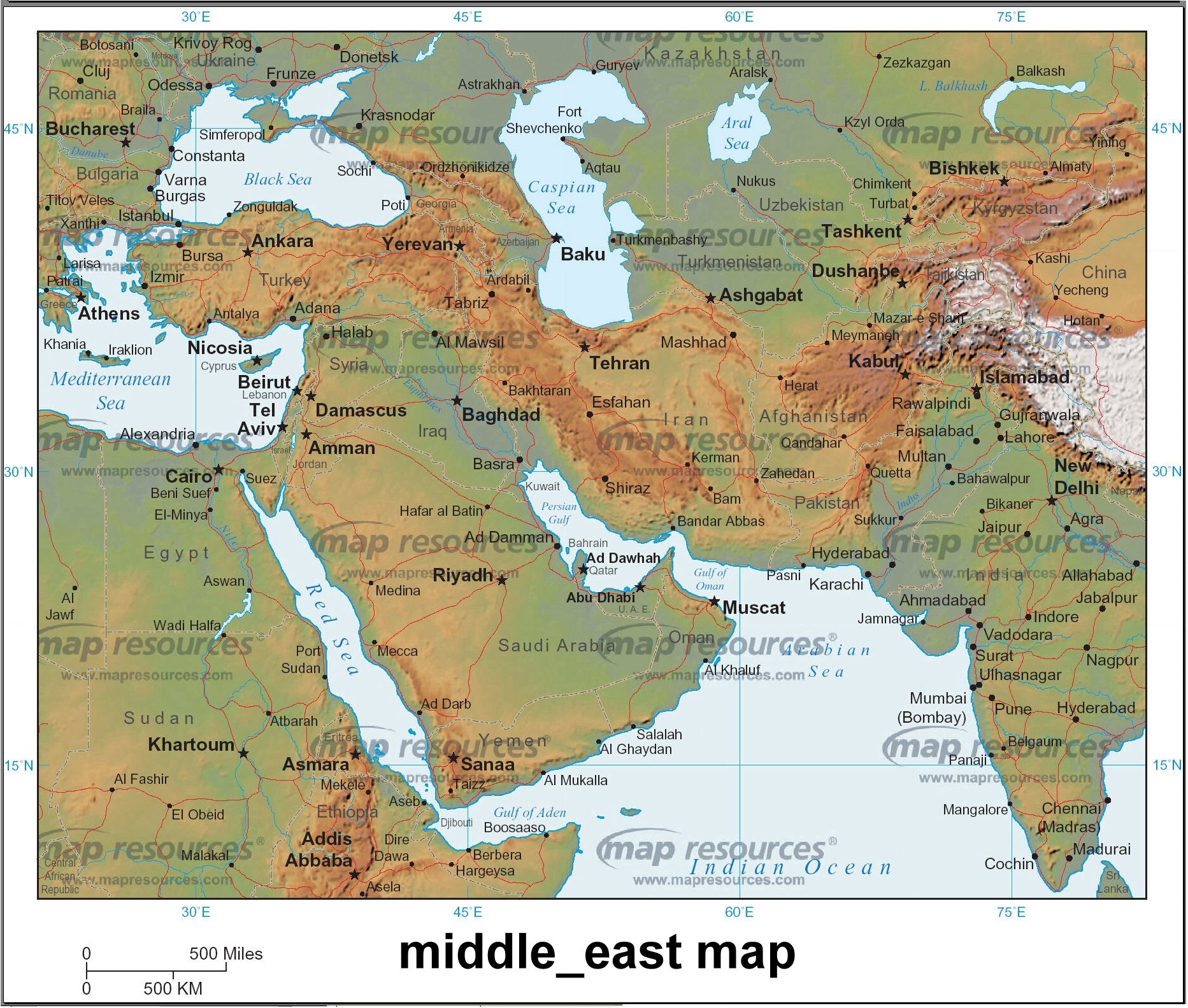

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was in the Middle East recently to, among other things, organize the Abu Dhabi Stake and the Bahrain District out of the Manama Bahrain Stake.

Latter-day Saints in the area has tripled, from 900 when the first stake was formed 28 years ago to 2,700 today, a division was needed. The original Arabian Peninsula Stake was organized by Elder Boyd K. Packer, now President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

Why didn’t I know there was a stake in the middle of the Middle East? I mean, do you know were Abu Dhabi is? Again, courtesy of the CIA:

When I say middle of the Middle East, I mean right in the middle:

After reading many, many arguments for rejecting faith in God–including some posted today in The Washington Post’s “On Belief” section–I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m safe in my belief. That is, I’ve yet to read any such argument that even begins to touch the pillars of my belief system, the pillars of my faith. Instead, doubters and the faithless, hack away at a straw man religious faith that is always foreign to me, so foreign, in fact, that I often find myself agreeing with the critic.

The following passage from Walter Russell Mead‘s essay, Establishment Blues, has caused me to think about and appreciate my faith more than anything I’ve read outside the scriptures in many moons:

The religion gap between the elite and the rest of the country is a big part of the problem — and in more ways than one. I can’t help but notice that the abandonment of serious religion by most of the American elite has coincided with a massive collapse in both the public and private morality of the American establishment. Kids who weren’t raised in church or synagogue or mosque, who were taught that ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ were simplistic categories in a complex moral world of shades of gray, who were told that their highest moral duty was to be true to their inner passions, who were the first generation in American history to be raised in a Scripture-free educational medium, turn into self-indulgent, corner-cutting, self-centered adults.

What a surprise! We raised a generation of bright kids without a foundation in religion, and they’ve grown up and gone to Wall Street. We never told them that the virtuous life was both necessary and hard, that character was something that had to be built step by step from youth, that moral weakness was both contemptible and natural: and we are shocked, shocked! when, placed in proximity to large sums of loose cash, they grab all they can.

Religion is no guarantee of righteousness; Elmer Gantry is not the only sticky-fingered preacher in the history of the world. But at least in western history when the culture and habits of mind of an entire social milieu have lost touch with their cultural foundations in ethical monotheism, trouble is usually on the way. The estrangement from religion is also an estrangement from the ideas and cultural values that bind society into a workable whole.

The French aristocrats laughed at the manners and the morals of the common people and ridiculed the faith that lit the darkness and softened the harsh conditions of ordinary lives. Enlightened and cosmopolitan, the establishment mocked the attachment of the ignorant peasants to the king. The well educated, well connected elites accepted no limits on their ability to convert their social privilege into personal wealth; they accepted no limits on the gratification of their physical desires — flaunting their romantic affairs in the same spirit in which they feasted at Versailles while the gaunt peasants starved. They used and abused to the fullest all the privileges that came with their status while mocking and rejecting any sense of duty and obligation.

It was fun while it lasted.

I’ve bolded the parts that have virtually been ringing in my ears since I first read the essay. I’m not sure why. Yes, what Mead says confirms my own beliefs, but the reason his thoughts have so impressed themselves upon mine must go beyond that. Maybe with a little more thought on my own, I can come up with the reason.

This I do know: I am thankful beyond measure for the faith of my father and mother, my grandfather and my grandmother, and–lucky me–my progenitors going as far back as my great-great grandparents on both sides. You see, my great-great grandfathers on both sides marched in the Mormon Battalion across the United States, into Mexico, and on to San Diego–well before The Beach Boys beckoned us all to Southern California. And then they walked back to Salt Lake City and, at least in the case of George Washington Taggart, walked on to Winter Quarters, Nebraska–prodded on by the faith that strengthens me daily.

I’ve been a fan of Christopher Hitchens for at least 10 years, largely because I agreed with his principled stand on Iraq. I’ve since learned that it’s possible he would take a similar stand if someone wanted to invade Utah. He doesn’t like my church, any church for that matter.

A churchman myself, I can turn the other cheek and allow him to slap away. I have this sneaky feeling that he’s a closet Christian. His brother Peter is a believer. What do I base this “feeling” on? Two things. The first was an article in The Washington Post (I think), wherein he talked about how he made sure his children read the Bible because it had such an influence on Western civilization. The second is his recent paen to the King James Bible in Vanity Faire, again for much the same reasons.

The God I believe in is great enough to forgive Christopher’s sins, once Christopher himself sees them.

If he–Hitchens, that is–has the towering intellect attributed to him, he’ll one day recognize them. In this, I disagree with his brother. It’s not the cancer that will bring Christopher to God. It’s the attendant humility.

God, after all, will have a humble people.

And with this, I almost forgot why I began this post. The reason, again in Vanity Faire, is Hitchen’s essay on losing his voice. Essays like this are one reason I respect the man. If he’d only not written that diatribe against my religion.

Peter Vidmar resigns as chief of mission for the 2012 U.S. Olympic team.

Why? you ask.

In a story on the Chicago Tribune’s website Thursday, openly gay figure skater and two-time Olympian Johnny Weir called Vidmar’s selection “disgraceful” because of Vidmar’s opposition to gay marriage.

Vidmar, a Mormon, was a public supporter of Proposition 8, the voter-approved law passed in 2008 that restricted marriage in California to one man and one woman. The Mormon church believes all sexual relations outside of marriage are wrong, and defines marriage as being between a man and a woman.

Kind of turns “do unto others” on its head.

Christ at Emmaus

One of them recoils

One buries his head in the Lord’s broad lap.

What would you do

if, mid-meal, light suddenly broke

from a body rather like your own

and a stranger suddenly became

in very flesh the friend you mourned?

You would be shocked, no doubt — horror,

amazement, joy, dismay competing,

no words available for the occasion.

You might embrace him, weeping, or grasp instead at some shred

of rationality while your pupils

contracted and your heart beat in your throat.

It might be harder than you think

to give up three days’ mourning,

memories already being edited and arranged.

The story had seemed complete.

Having a tale to tell, you might already

have found a way to tell it whole,

rich with mystery, rounded and

resonant with meaning.

You might have been ready

to go back home, tired of all that wandering,

ready to sit at the lakeside and take up

the nets again, writing a little, keeping

your counsel, sharing a parable now and then

with those who had seen him once,

who remembered the picnic on the hillside —

all that bread and fish.

You would have had to give up yet again

what you thought you had a right to claim.

Turns out he meant it — the promise

you’d already begun to turn to metaphor.

Here in dazzling flesh, leaning back

to let himself be seen, he leaves them no choice

but to lay aside sweet sorrow and cancel all their plans

for the aftermath.

from Drawn to the Light: Poems on Rembrandt’s Religious Paintings by Marilyn Chandler McEntyre.

Panorama Theme by ![]() Themocracy

Themocracy